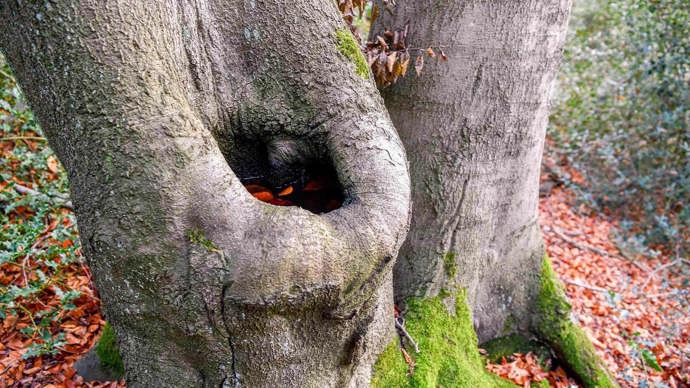

Credit: Ben Lee / WTML

Why are microhabitats important?

Microhabitats are the secret to woodlands that thrum and pulse with life. From pollinating plants to decomposing deadwood, every species plays a unique and important role in the woodland ecosystem. Each of these species has different needs, so a wood brimming with a diverse range of microhabitats can provide refuge, breeding, wintering and feeding spots for a wonderful array of woodland wildlife.